(As seen in Green Living Magazine, Oct. 2013 – greenlivingaz.com)

(As seen in Green Living Magazine, Oct. 2013 – greenlivingaz.com)

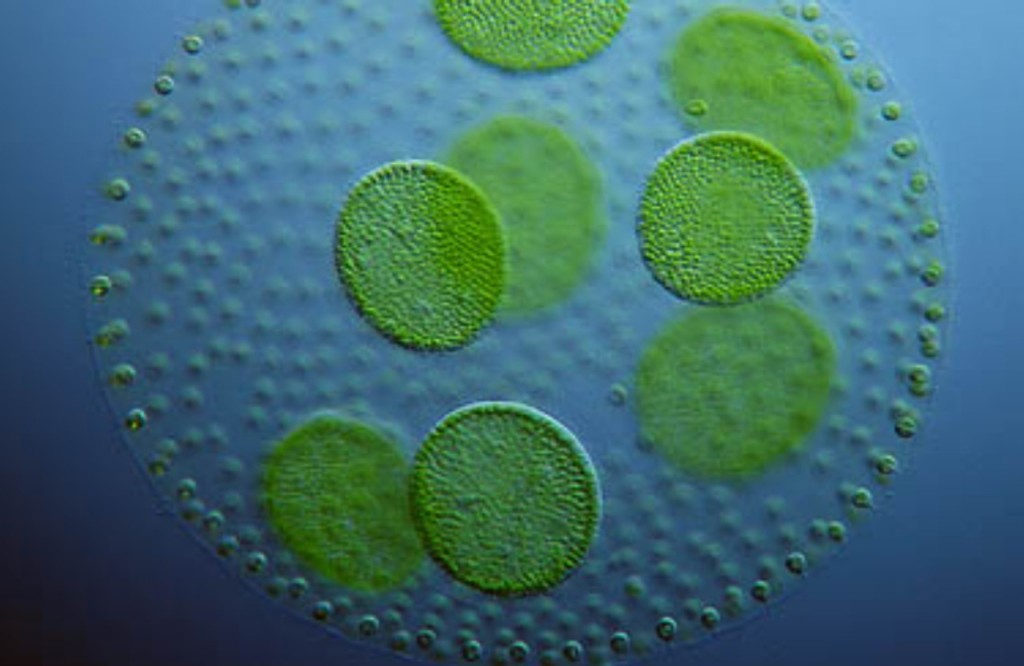

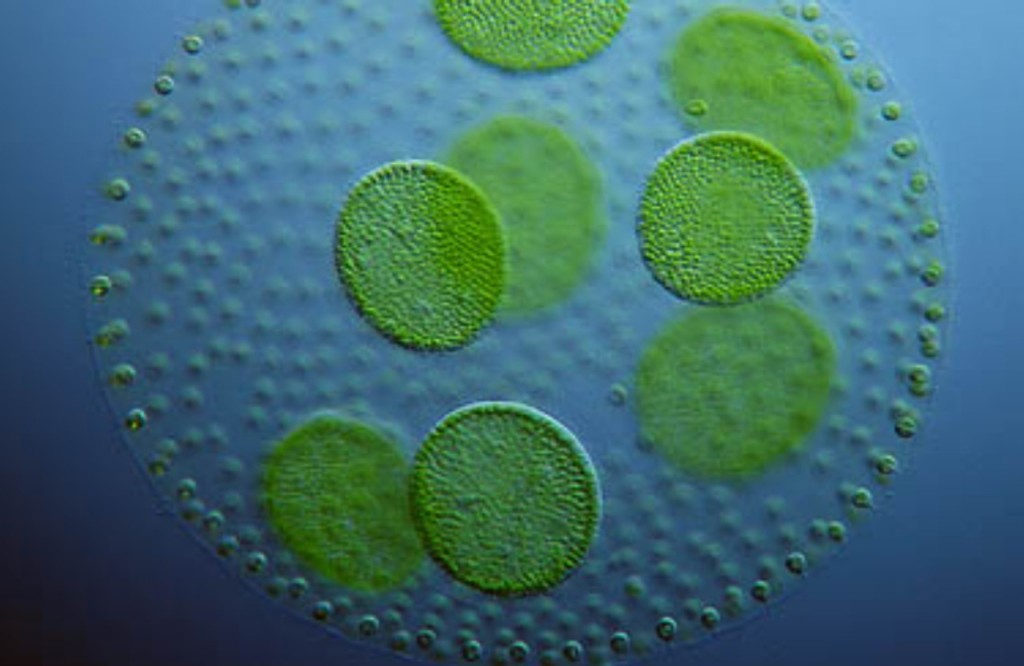

If a person thinks of algae, they mostly likely think it’s time to clean the pool. But there is a place in Mesa that concentrates on growing the stuff on purpose. The Arizona Center for Algae Technology and Innovation (AzCATI), a part of the College of Technology and Innovation on the Arizona State University’s Polytechnic campus in Mesa, is dedicated to researching the uses for those little green organisms.

When I asked Dr. Milton Sommerfeld, professor and co-director of AZCATI, about the difference between what clouds up the swimming pool and what the lab grows in giant test tubes, he says, “It’s essentially the same thing. One of the best strains in terms of petroleum was isolated from a small pond in Phoenix.”

Striking Oil

For years, the big story about algae is about turning it into biofuel. According to Sommerfeld, about 50 percent of some algae strains are oil. He provides a brief history lesson: In the late 1970s, the government realized that the country had become too dependent on foreign oil and initiated the Aquatic Species Program, an effort to research algae as a potential oil source. He and others went out bio-prospecting throughout the Southwest, identified as desirable because of its sunny climate.

Oil extracted from algae looks like dark crude oil. When processed into biodiesel, it’s as clear and gold as the vegetable oil in the pantry. (It even smells like vegetable oil.) Unfortunately, although research findings continue to look positive, he says that developing a fuel product to compete in a commodity market is challenging and that while we’ve been extracting oil for more than 100 years, research on biofuels is relatively new.

You’re Already Eating It

To illustrate the diverse range of products that contain algae, Sommerfeld has a line of containers on his desk. He holds up two jars – one with dark green powder, one with lighter green powder. Both are biomass, what’s left of algae once either water or oil has been extracted. This is the stuff that is rich with protein and carbohydrate and is put in health supplements, or used by his wife for algae cookies.

Even if you’re not a health-food-healthie, you’ve probably been consuming algae without knowing it. Sommerfeld hands over an empty ice cream carton with the ingredient carrageenan circled, explaining that anything a food producer wants to be creamy (including ice cream, yogurt, cottage cheese, salad dressing or even the head of foam on beer) contains a by-product of red algae, agar or algenic acid.

Algae is not only a source of fuel oil, but a source of omega 3 fatty acids, what most of us call fish oil. The latest health supplement, derived from red algae, is astaxanthin (ast-a-zan-thin), a powerful anti-oxidant.

Cool Clear Water

When research on algae started in the Southwest, researchers were using highly saline aquifer water. The idea was to find environments in which the algae would survive. What has evolved it using algae to assist in water purification processes. AZCATI uses various waste water sources to test how algae absorbs nitrogen and phosphorous from effluent and gray water. Once the organism has eaten its fill, so to speak, it can be used for fertilizer. Sommerfeld hopes that in the future, farmers use and re-use algae as a soil amendment, cutting down on synthetic fertilizers that create unhealthy run-off.

In the Field

The AZCATI facility looks like any other office or classroom building, full of offices and labs, including a small room full of very technical-looking devices that Sommerfeld calls the million dollar room. We pass through areas where men and women in lab coats examine slides, and test tubes the size of packing cylinders bubble. This is where algae strains are identified and tested. Depending on the results, they get promoted to be tested outside.

Across the street behind a high fence are shallow pools in sizes small, medium and large equipped with paddlewheels to keep the algae moving and exposed to light. Farther back, in 50-foot rows, are panels approximately four feet tall and three inches wide, slim acrylic sandwiches full of bubbling fluid in various shades of green. Once the algae appears nearly black, it’s ready to harvest and process further. Not far away is a field lab where further testing is done.

And Beyond

AzCATI’s doesn’t exist in a vacuum, however. Although the center is part of ASU, it is dedicated to serve as a place for research, testing and the eventual commercialization of algae-based products, providing open test and evaluation facilities for the algae industry and research community. Sommerfeld explains that the goal is to have “universities, national labs, industries come here and collaborate with us and to, in a sense, build the innovation base that we need for an algae industry.”